YALI Staff Reflection: Shifting Perspectives

Editor’s Note: Adrienne was a Summer Program Fellow for the Presidential Precinct while YALI 2017 Fellows were in Virginia. She not only had the opportunity to work with the Fellows, but also got to live with them throughout the six-week Fellowship. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and not those of the Presidential Precinct, its partners, or donors.

One thing I’ve learned from living abroad is that the best way to learn about a country is to talk to the people who live there. Although it’s important to see places first hand, it’s not always easy to find the money to travel and going to a place uninformed can lead to misunderstandings. On the other hand, trying to research on your own can also be difficult. History books and news articles are often politicized, and the views they portray can be detached and impersonal. For me, it’s not until I listen to stories from people who know the country and have lived through its experiences that I really begin to understand.

When I found a posting online about a position that would allow me to live with twenty-five Africans for six weeks, I was thrilled. I couldn’t wait to learn about their countries and hear about their lives. I wanted to know about their perspectives of the world, and how they saw their own countries within a global setting. I wondered what they would find strange about America, and what similarities there were between our countries.

Indeed, meeting the Washington Mandela Fellows was incredible. I put names and faces to countries that I had never been to before. I listened to the problems they faced and the solutions they discovered. I learned about their cultures through foods and music they shared with me. Every day I learned more from them. And every day I felt inspired by their determination to make the world better.

But what surprised me the most was how much I learned about America during those six weeks. After living in Asia for the past three years and living in Canada for ten years before that, I had forgotten a lot about the country where I was born and had first grown up. In the process of introducing the Fellows to America, I was also reacquainting myself with the United States as an adult.

For the first time, I saw the presidential homes of Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe. For the first time, I went to a rodeo and saw cowgirls doing barrel races. For the first time, I saw a naturalization ceremony welcoming new American citizens into the country.

And for the first time, I started examining the narratives we tell about slavery.

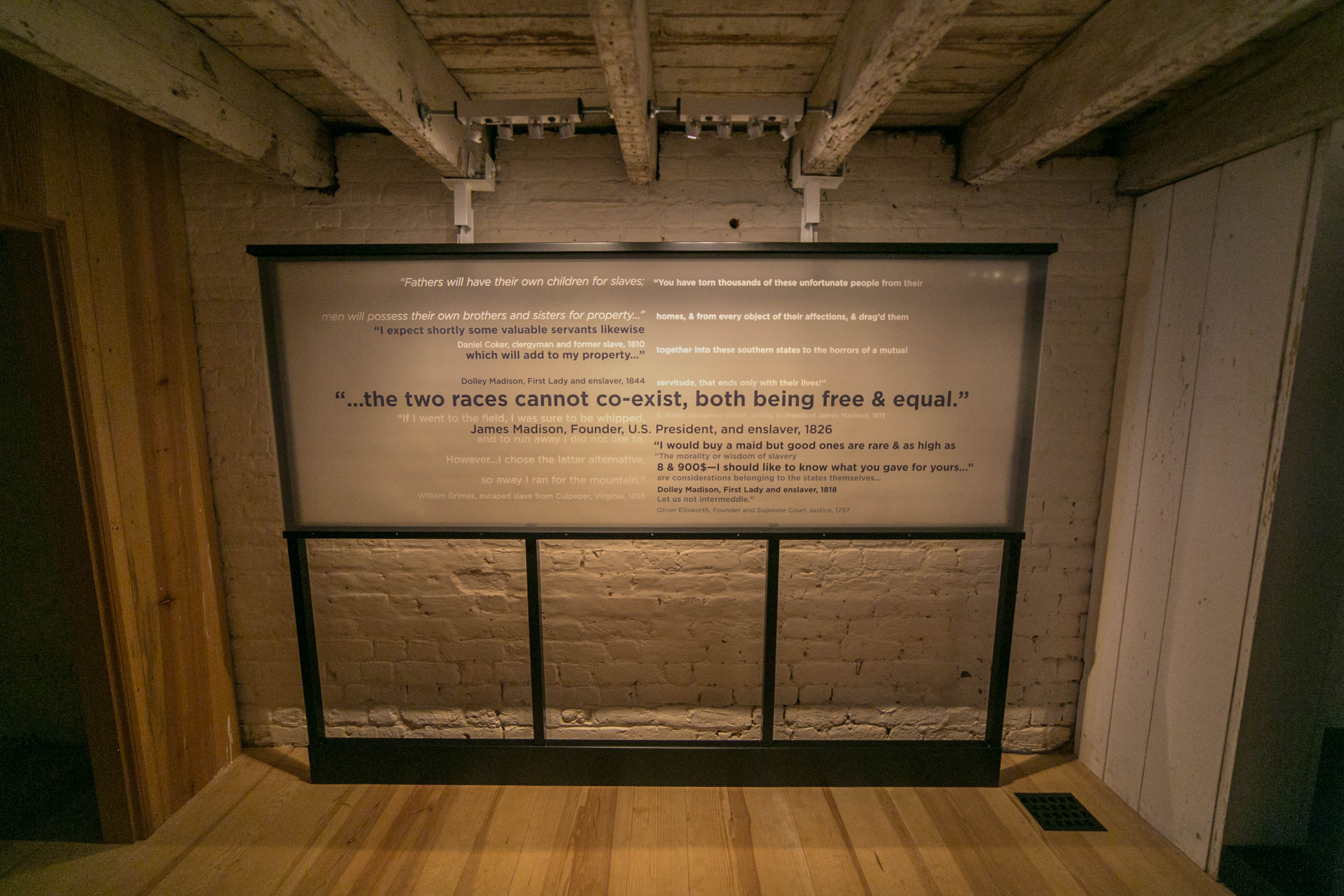

The Mere Distinction of Colour, James Madison’s Montpelier

When I was in elementary school in Boston, we learned about the Civil War. We knew about Harriet Tubman and her bravery in leading slaves through the Underground Railroad. But most of all, we were taught that racism was over. In the past there were slaves, and in the past the races were segregated, but now everyone is truly equal. The history of our country was laid out simply, with clear heroes and villains. We didn’t talk about racism or even acknowledge the hypocrisy of creating a free nation that enslaved millions of people. And as an Asian American, I honestly didn’t think too much about it.

Remembering my childhood, I was amazed to see how much progress had been made in addressing our nation’s shameful past. At Monticello, there was talk about the upcoming Sally Hemmings exhibition. At Montpelier, a recently opened slavery exhibit called ‘The Mere Distinction of Colour’. And both the University of Virginia and William & Mary were candid about the role slaves had played in the construction of their universities.

All the sites we visited with the Fellows kept the issue of slavery front and center, and I was excited to see that institutions were opening up a dialogue about racism and slavery.

The Fellows, however, weren’t as thrilled as I was about our progress.

“How can the Founding Fathers believe that all men were created equal, yet own slaves,” they asked. “Why do you keep telling us to consider the historical context? It doesn’t matter how well a master treated his slaves; they were still slaves.”

The Mere Distinction of Colour, James Madison’s Montpelier

Hearing the Fellows speak, I realized that I was guilty of this too. We say that slavery is wrong, that we’re glad that it ended and that it should have ended sooner. Yet at the same time we try to justify and romanticize slavery when we look at our forefathers. We make excuses for them about how they knew that slavery was wrong, but they continued to own slaves as they struggled to find a way of ending it.

I’m still impressed by how far we’ve come in talking about these issues. Over the years, many people have worked hard to make sure that African American stories are part of the landscape of our historical sites. At the same time, we need to keep looking forward to the changes that still need to happen. As Americans, all of us have a responsibility to do what we can to truly end the systemic racism that has -and continues- to plague our country. Sharing narratives that have been lost in history is an essential starting point for future change.

While living in Japan, I often felt frustrated when I saw the U.S. in the news. I didn’t agree with the xenophobic and isolationist rhetoric being promoted in the press and I felt like I didn’t know the country I had been born in anymore. Where were the values of inclusion and tolerance that I had loved so much? How could America turn its back on immigration when immigrants founded it? I felt like the progress we had made was unraveling and I was powerless to stop it.

But what seems impossible on your own becomes possible with the help of others. People often talk about the strength of institutions, but those institutions are made up of individuals. Living abroad, watching as an outsider, I only thought about how the United States didn’t reflect who I was. I was passively waiting for the country to change, hoping to have my beliefs represented and wondering what other people were doing to help. But during my time with the Presidential Precinct, I discovered so many remarkable nonprofit organizations, and so many committed people working to uphold the ideals that I thought were being destroyed. While I was waiting for change to happen, countless people were actively working to protect their visions of America.

None of the Fellows pretended that their countries were perfect. Instead, they used their knowledge of those imperfections to help people and improve lives. And that’s what we all need to do if we want a different future. As citizens we have the right -and responsibility- to shape our country to reflect the values that are important to us. If we’re dissatisfied with our country, then the solution is not to run away, but to help catalyze positive changes.