CAMILA ROA YÁÑEZ: Latin America’s Beacon for Young Leaders

A land of contrasts

Chile occupies a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west. It is the southernmost country in the world and the one closest to Antarctica. Its peculiar geography makes it an extremely diverse country in terms of weather, landscapes, resources and needs. Despite its rich diversity throughout its 16 regions, it is still heavily centralized.

Chile is known for being a developing country with a high-income economy, leading Latin America’s rankings of competitiveness, per-capita income, among others. In contrast, according to the OECD it’s one of the three most socially unequal countries in the world. Sometimes, numbers on rankings do not reflect reality, as illustrated by the Chilean Poet Nicanor Parra:

“There are two pieces of bread. You eat two. I eat none. Average consumption: one piece of bread per person”.

The citizens of Chile had long expected this dichotomy to change after the return to democracy in 1990, but instead, feelings of social injustice brewed for nearly 30 years. This resulted in a “social outburst” in October 2019 with protests led by secondary students, speaking out against an increase of the subway fare by 30 pesos. People all over the country joined the protests adding more demands such as better education, equal access to health, a new social pension system and natural resources protection, among others.

During this period of social unrest, people began to meet at public places to discuss their demands. Public squares, neighborhoods, parks were spaces where citizens would join together to talk about the roots of inequality, teach themselves about politics and discuss possible paths to solve some of these demands. Civic engagement was widespread! But despite our democratic governments’ best attempts to make social improvements, inequality kept growing. These governments’ attempts were always limited by our 1980s constitution, written by our former dictator Augusto Pinochet and five of his closest allies.

As protests continued, a new demand absorbed all the others: A new constitution, written by the people and for the people.

On November 15, 2019, Chile’s National Congress signed an agreement to hold a national referendum that would rewrite the constitution if it were to be approved. On October 25, 2020, Chileans voted 78.28% in favor of a new constitution.

An election for the members of the Constitutional Convention was held between May 15 and 16, 2021.

Boric: A record beating president

In this political context, a young yet proven leader named Gabriel Boric began his campaign for president of Chile. He participated in protests in 2011 demanding for better and more affordable education as a student leader. He was also part of the political negotiations for a constitutional agreement and a leader committed to feminism, decentralization (living himself in the Southernmost region before Antarctica), LGTBQ+ community rights, and the social demands that emerged during the last couple of years. In many ways, Boric was positioned as an ally to those demanding social change – his candidacy an opportunity for true change in Chile’s future.

On December 19, 2021, 35-year-old Boric was elected president of Chile with 55.86% of the vote and beat many records: he’s the youngest president Chile has ever had and he obtained a higher percentage of the vote than any past president. The 2021 election also drew the highest participation since the beginning of our voluntary voting system.

A few weeks ago, Boric presented his cabinet. 14 out of 24 ministries will be led by women and 7 out of 24 ministers do not belong to any political party.

Chileans hold great expectations for this government, who’s president-elect has promised to mend the causes of social injustice in Chile. This government starts in the middle of an economic crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and will be holding a referendum to vote on the newly written constitution during Boric’s inauguration year. Boric’s challenge will be to find a balance between economic growth and social welfare and to conciliate ideas in such a historically politically polarized country.

A new approach to democracy

During my time at the Presidential Precinct for the 2019 Global Pathfinder Summit (just a few months before Chile’s “Social Outburst”) I had the chance to hold long conversations with young leaders of all the world. We had so many issues in common: an increasing lack of confidence in political parties and the desire to find a way to improve and strengthen our democracies.

During the GPS we came out with a plan to tackle our political crises. We agreed “to foster civic engagement in our communities, educate our fellow citizens about the power and promise of civic engagement to solve societal, political and cultural challenges; and personally commit to take action to foster engagement among all citizens in our home communities, states and nations.” (The Virginia Resolutions, May 2019)

When I first came back to Chile, I was immediately discouraged by the lack of instances where I could take action and carry out these resolutions.

And then, when the social protests happened, everything changed. As if all the fellows I had met predicted it: good governance must include citizen engagement; otherwise, trust in politics could not be possible.

I realized how important it was to make citizens aware of the relevance of politics in our lives and how engaging in the process could lead to betterment in society.

A sociologist friend of mine and I met together every week to study our constitution. Then, we would translate it into a simpler more legible language, better understood within our community. We researched how other countries have managed to change their constitution and what pros and cons are there in a process like this. We shared every useful information we found. Without even noticing, I was taking action just as we stated in the Virginia Resolutions. But it was not only us. It was happening all over the country.

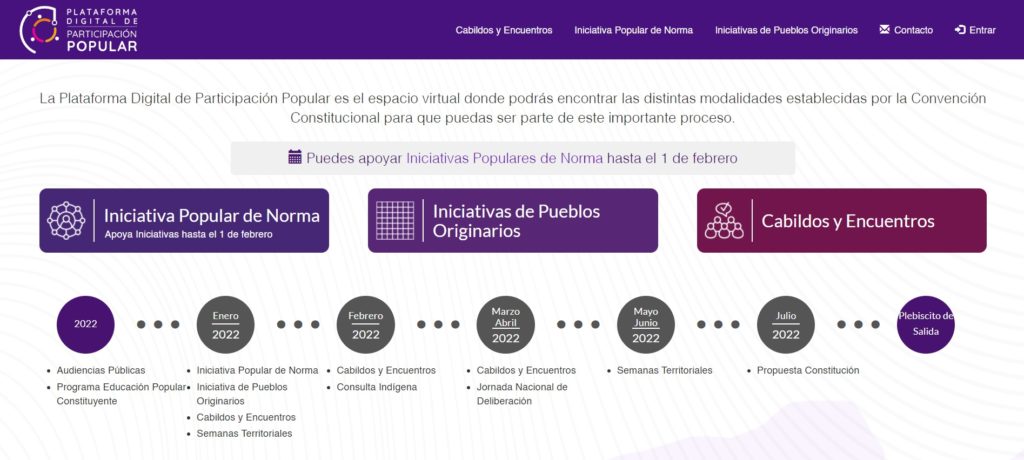

New ways of engagement have since emerged, such as a digital platform created by the representatives of the constitutional convention, where people can vote for initiatives regarding issues that should be considered in the constitution. Issues that receive the most voted will then be discussed in the convention.

Through this process, I have discovered that citizen engagement and participative, direct democracy is the only way to rebuild trust in politics, and that without this, the political class could never achieve a wide understanding of people’s needs and wishes for a more prosperous society. It’s crucial for governments to provide spaces for participative democracy. And then of course, it’s crucial for us young leaders to be ready to respond, engage and model civic engagement in our communities all over the world.